Emancipation allowed a small number of family members, who had been separated during enslavement, to be reunited. According to the Antiguan labourer Samuel Smith (1877-1982), ‘People badly want to unite with the family – particularly the womankind. I hear that the women was [sic] furious and desperate to find their people.’ There were strong feelings about the care of the elderly and the need for children to be kept from working on the plantations. African family units were cohesive: ‘There is a connexion of the negroes that is not generally known in this country; that is, as godfathers and godmothers, which is as binding as the relation of the parents themselves.’ (Select Committee 1842, para. 1280)

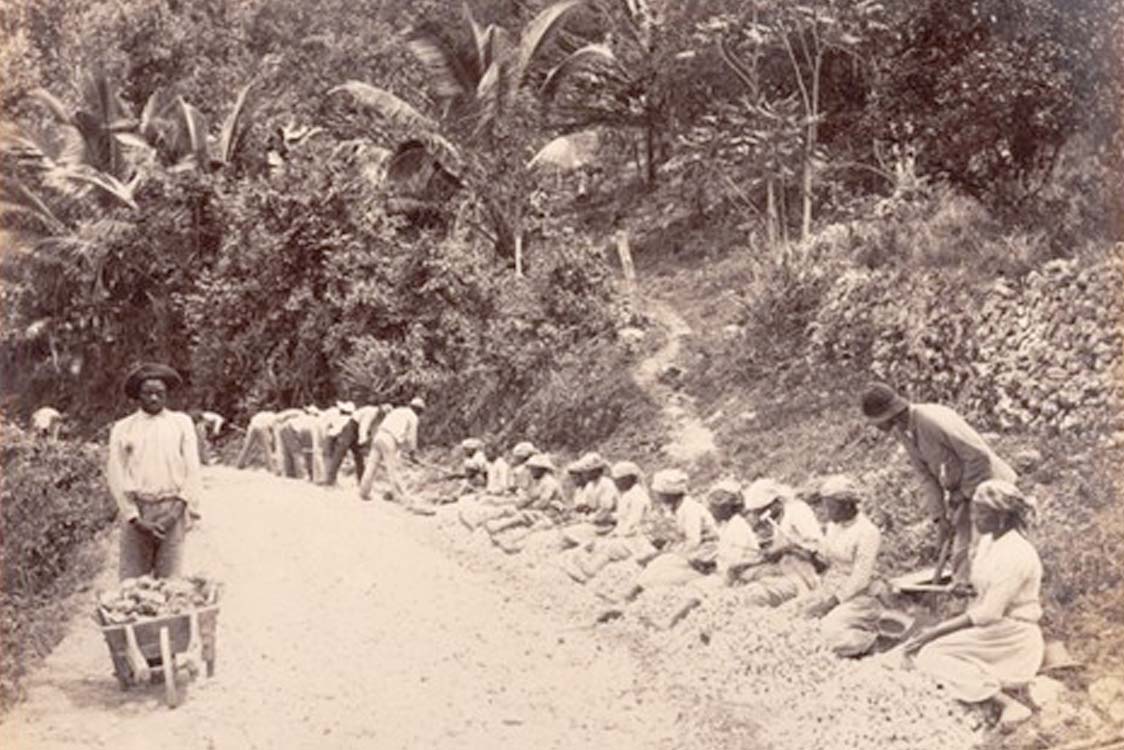

For nearly 100 years after full emancipation in 1838, employers in the Caribbean kept wages below the bread-line, adversely affecting African family life. The men were often employed three days a week, and struggled to meet the needs of family members. Some women obtained low-paid domestic work, and many others worked in the fields alongside the men. Middle class African families (a small minority) who were usually skilled workers, ensured that their children obtained educational and professional occupations that fitted them for important roles in the colonies. Working class Africans lived in homes that were generally below minimum standards; middle class ‘coloured’ family members (a larger minority) were the ones most likely to occupy the positions of power in Caribbean colonies.