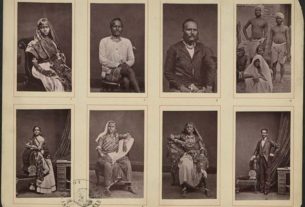

The end of enslavement in 1838 saw the enactment of laws that severely restricted the rights of labourers, making the formation of workers’ organisations a criminal offence. Some laws prevented them from owning land or property. Fines, physical punishment, imprisonment or eviction from homes could be imposed for breaking the laws.

The economic situation for the vast majority of the Caribbean population by the end of the 1800s and early 1900s showed little difference to that which was imposed on them by planters before 1838. It was an era that had seen two industrial revolutions in Britain, and huge profits made by British companies, but at the expense of African workers. The worsening conditions in the Caribbean led to fewer opportunities to emigrate. Government refusal to recognise workers’ organisations, and an unwillingness to accept the old colonial order, led to widespread strikes, riots and distress throughout the region. The British Government had no alternative but to appoint the West Indian Commission of Enquiry (headed by Lord Moyne) in 1938 to investigate the situation there. The Commission’s Report was so damning of the conditions of the vast majority of Caribbean people that it was suppressed until after the end of WWII for fear of fuelling German propaganda against Britain.

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and the African Communities League led by Marcus Garvey became sources of inspiration for Africans in the Caribbean during this period.